Critique and Conspiracy

How can we distinguish between problematic or dangerous conspiracy theories and legitimate intellectual critique?

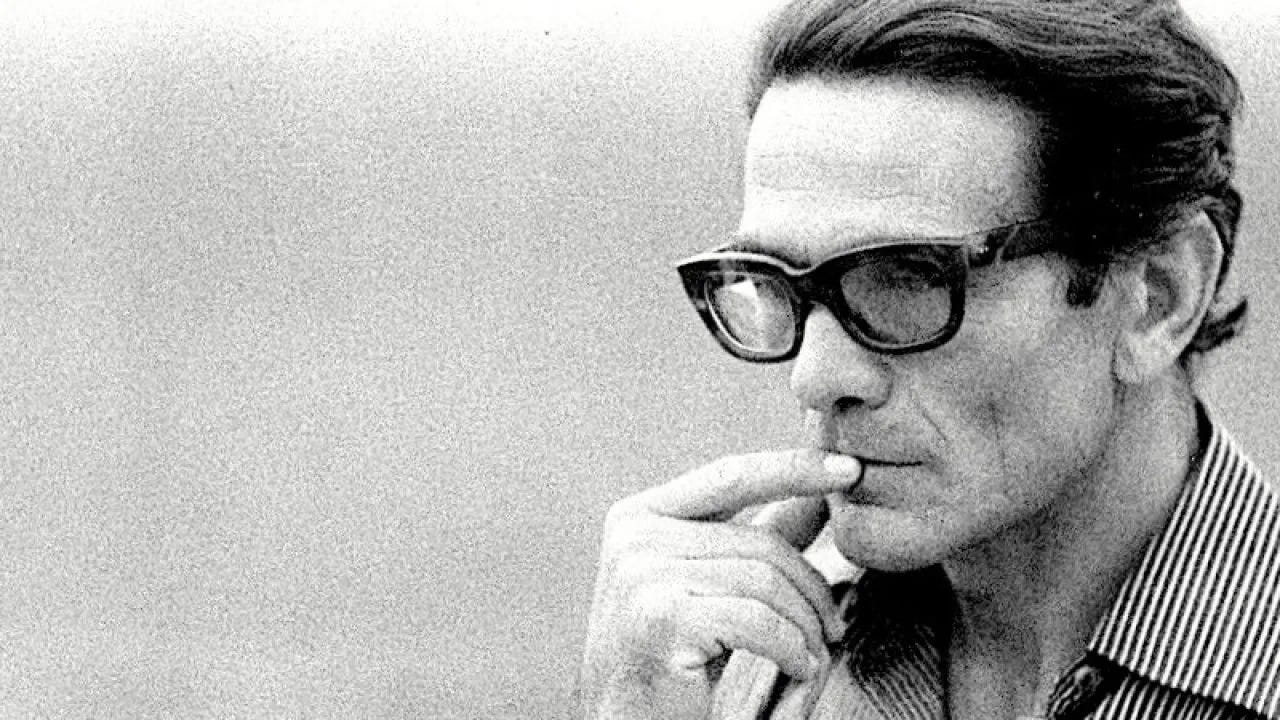

Has there ever been a more magnificently paranoid vision of intellectual activity than that offered by the Italian leftist thinker Pier Paolo Pasolini in one of his final texts, “Is this a Military Coup D’Etat? I Know…”?

In the article, published a year before his murder, Pasolini declared his knowledge of societal secrets in a series of incantatory declarations: “I know […]. I know […]. I know […].” Among other things, Pasolini claimed to know the names of those responsible for various far-right “massacres”: in Milan in 1969, and in Brescia and Bologna in 1974; Pasolini also claimed to know the names of a “group of powerful men who, with the help of the CIA” initiated an “anticommunist crusade to halt the ’68 movement.”

So how had Pasolini come to know these things? Writing more programmatically, he declared:

I know because I’m an intellectual, a writer who tries to keep track of everything that happens, to know everything that is written, to imagine everything that is unknown or goes unsaid. I’m a person who coordinates even the most remote facts, who pieces together the disorganized and fragmentary bits of a whole, coherent political scene, who re-establishes logic where chance, folly, and mystery seem to reign.

This was a vision of the intellectual-as-seer, one who assembles all the relevant facts, passed over unnoticed by the majority, to penetrate beneath mere surface appearances in order to reveal the secret links between phenomena and their undisclosed causes. The intellectual is the one who sees what others do not, who finds telling signs where others see nothing out of the ordinary.

But is there any difference, even in principle, between this basic critical-intellectual stance, and that classic Hollywood portrayal of paranoia, A Beautiful Mind (2001)? In the movie, we realize that Russell Crowe’s character, the mathematician John Nash, has fallen into delusion when we see what has become of his office: Hundreds of newspaper clippings are pinned to the walls, connected by threads of colored yarn—a “network” of furtive nodes and mystical vertices, revealing that which ordinary citizens have failed to comprehend, lacking as they do Nash’s piercing gnosis—his secret knowledge and insight.

Something similar appears—but more entertainingly, less tragically—in the dizzying opening montage of the film Conspiracy Theory (1997). Here the protagonist, Jerry Fletcher, a New York taxi driver played by Mel Gibson, launches into a series of semi-deranged conspiracy theories as he ferries his unsuspecting passengers around Manhattan. Fletcher’s theories range from the role of the Vatican to microchips, via “black helicopters” (“They’re everywhere.. You can’t hear them until they've already gone.”), to the fluoridation of drinking water:

You know what they put in the water, don’t you? Fluoride! Yeah, fluoride. On the pretext that it strengthens your teeth! That’s ridiculous! You know what this stuff does to you? It actually weakens your will...Takes away the capacity for free and creative thought, and makes you a slave to the state.

The ironies of history are rife here. Fourteen years later, the U.S. government reportedly deployed a pair of “stealth helicopters,” or heavily-modified Sikorsky UH-60 Black Hawks, to kill Osama bin Laden, ascending onto his Pakistani compound almost unnoticed. Meanwhile, some research does suggest that water fluoridation can indeed be harmful to some groups, such as pregnant women, as the New York Times recently reported (with multiple caveats). And in a final bizarre twist of life imitating art, Mel Gibson himself would fall from grace some years later for espousing a vile antisemitic conspiracy theory, stating to the police officers that were apprehending him, “The Jews are responsible for all the wars in the world,” according to The Guardian.

From Pandemic to “Infodemic”

Clearly, conspiracy theories can be deeply troubling. At best, they are a nuisance and a distraction; at their worst, they can lead to pogroms and genocide. They are, in the words of the philosopher Frank Ruda, “problematic manifestations of a rational demand, a demand of reason.” As he writes, “This demand is a demand for orientation in a world that no longer allows for any, since the constitutive principles of its organization have become obscured.” In the chaos and complexity of the world, conspiracy theories provide the appearance of order, clarity, and coherence; they offer reassurance that an often incomprehensible world can be made simple and intelligible. But they also often satisfy an appetite for an easily identifiable “enemy” onto which all the ills of the world can be heaped—a form of social misdiagnosis.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, conspiracy theories seemed to gain in importance. Far from being mere irritants, the very future of the world now seemed to hang on the ability of governments to do battle with the ideas of “anti-vaxxers.” The World Health Organization went so far as to declare an informational epidemic, or “infodemic,” alongside the viral pandemic, in late 2020. Hazy ideas about 5G towers, microchips, and billionaires like Bill Gates had circulated on social media for years, without much effect on global events. Now, however, conspiratorial anti-vaxxers rose in stature: They seemed to stand a real chance of blocking the resumption of normal everyday life on a planetary scale by preventing the mass rollout of vaccines like Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech.

In August 2020, UNESCO and others launched a campaign to “raise awareness of the existence and consequences of conspiracy theories linked to the COVID-19 crisis.” Fact-checking websites and features became increasingly commonplace. By early 2021, Twitter introduced its “Community Notes” feature, allowing for added context on popular but controversial posts. The European Commission, meanwhile, outlined six features of a conspiracy theory:

An alleged, secret plot.

A group of conspirators.

‘Evidence’ that seems to support the conspiracy theory.

They falsely suggest that nothing happens by accident and that there are no coincidences; nothing is as it appears and everything is connected.

They divide the world into good or bad.

They scapegoat people and groups.

Definitional Dangers

However, this war on conspiratorial reasoning comes at a cost. First, we should also inquire about the political-economic conditions that provide fertile soil for conspiratorial thought. Too often, the problem is construed in purely communicative, epistemic terms, when material conditions like social insecurity are responsible for providing the perfect breeding ground for these narratives. Improving people’s life chances—by raising social safety—is likely to be far more effective than banning and canceling utterances. At root, this is a problem of social insecurity.

Second, even a cursory inspection of the six features outlined above suggests potential overlap with the routine legitimate activities of, say, investigative journalism, critical social science, or intellectual critique. For instance, “An alleged secret plot” and “A group of conspirators”: But sometimes there really are plots in the straightforward sense of individuals or groups coming together to plan and organize an outcome aligning with their interests. Or: “‘Evidence’ that seems to support the conspiracy theory”: But quite often, what counts as evidence is itself subject to debate; the so-called “criterion problem” means that the standards of factuality that have to be met are part and parcel of debates over particular issues.

Or consider the feature, “Nothing is as it appears and everything is connected”: Certainly, there is an element of exaggeration here, but is this not a near-perfect encapsulation of what Paul Ricœur called the hermeneutics of suspicion, manifested in each their own way by the three giants of modern critical thought: Marx, Nietzsche, and Freud? In his writings on the parapraxes, for instance, Freud suggests that (almost) nothing we might blurt out is accidental; every slip of the tongue has its origins in the unconscious. Meanwhile, Marx, while not necessarily scapegoating, certainly does ascribe significant agentic power to the capitalist class, castigating it for exploiting workers; the state, on Marx and Engels’s account, is nothing “but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie.”

Closer to the contemporary world, when social scientists try to reveal the connections between power, social structures, and life outcomes—an ambition that encompasses critical sociologists like C. Wright Mills, Pierre Bourdieu, and many more—they do tend to suggest that “nothing happens by accident” and that, indeed, “nothing is as it appears”—because we live in a world of ideological figments, amidst the workings of symbolic power and doxa as well as the collective behavior of powerful social elites.

As for dividing the world into “good and bad”—I recall a senior social scientist once cautioning against using the very term “elites” in a draft paper because the rhetoric of “elites,” it seemed to him, was politically inflected—both from the left and right. But this is troubling: There really are elites, and their actions and attitudes matter; these are sociological facts, whether we like them or not. Certainly, we shouldn’t scapegoat elites; but where do we draw the line between a legitimate calling-out of the power of social elites, say, and what they themselves might describe as malign mistreatment? In Norwegian public debate in recent years, for instance, the Labour-led government has been attacked by business owners for its rhetoric about the importance of taxing the wealthy, which some have dismissed as “hatred and jealousy” of a particular class of people: the rich.

Return of the Dismissed

Moreover, acts labeled and dismissed as conspiracies can sometimes undergo a strange reversal of fortune: In the early stages of the pandemic, the Wuhan “lab leak” theory was dismissed as reckless, conspiratorial speculation, failing to accept the random meaninglessness of natural life and the inherent dangers of zoonosis. While early on in the pandemic Facebook censored lab leak posts, by May 2021 it had reversed its policy; at the time, the company said its change its “comes ‘in light of ongoing investigations into the origin’.” Three years after the pandemic began, the New York Times noted that while the idea of a Chinese “lab leak was once dismissed by many as a conspiracy theory,” the idea was now “gaining traction.”

The point is not that the lab leak hypothesis is necessarily true; most likely, it isn’t. Our desire for its truth may be fed by a need for clear agency and unequivocal responsibility, where instead we face what amounts to “a series of unfortunate events.” But all of this does point to the difficulty of establishing clear, rigorous, unassailable definitions of conspiracy theories, when something that “everyone” agreed was a conspiracy only a few years later is given a fair hearing in respectable broadsheets.

Counteract—Without Concepts

So are conspiracy theories destined to remain resistant to “objective” or rigorous definition—a case of “I know it when I see it,” as Justice Potter Stewart put it in his famous 1964 Supreme Court opinion on obscenity? Probably. Attempting to create a general, universal definition risks sweeping up legitimate intellectual activities within a broader definitional scope. The definition above, for instance, though well-intentioned, could plausibly be used to dismiss somewhat simplistic but still-legitimate social analysis.

This is not to say that we should run out and accept any old thing we are told. Nor does it mean we should quietly accept what we might perceive as nonsensical or dangerous claims about events, phenomena or groups. Instead, it means that we cannot define ourselves away from the hard work of countering these claims on the terrain of evidence, and where relevant, clear argumentation, including moral arguments. If we don’t agree with or like conspiratorial claims (which do not, in any case, as a rule meet the higher threshold of a “theory,” it must be said), or if we find them not only repulsive but downright dangerous, we should rather confront them head-on—not nullify, cancel, or censor them through conceptual moves that seek to “out-classify” them.

Certainly, some of these claims will be of such a nature that we may safely choose to ignore them, because of their marginality and/or preposterousness—which is not the same as censorship but rather a prioritization of effort. The work is great and the laborers few. And some may fall under the heading of hate speech, which is a different legal question altogether, to be dealt with by whatever procedures a particular society might have chosen for this category of utterances.

But by and large, we should not be afraid to counter conspiracy theories using all the intellectual tools at our disposal.

Only then can we say, like Pasolini, that “we know,” that we too have “piece[d] together the disorganized and fragmentary bits of a whole”—and made an honest attempt at understanding the totality, without lapsing into either paranoia or delusion.

Veldig fin tekst!

Hello Victor! I’ve been on here just over a week, and I’m trying to meet interesting new people, so I thought I’d comment.

I share a philosophical look into historic books, sharing what some call “alternative” history.

My latest article is about Tartaria:

https://open.substack.com/pub/jordannuttall/p/the-erasure-of-tartaria?r=4f55i2&utm_medium=ios