How to Buy Power and Influence People

Musk's Twitter takeover makes little business sense, but it has given the world's richest man a global megaphone and easy access to Trump's incoming second White House.

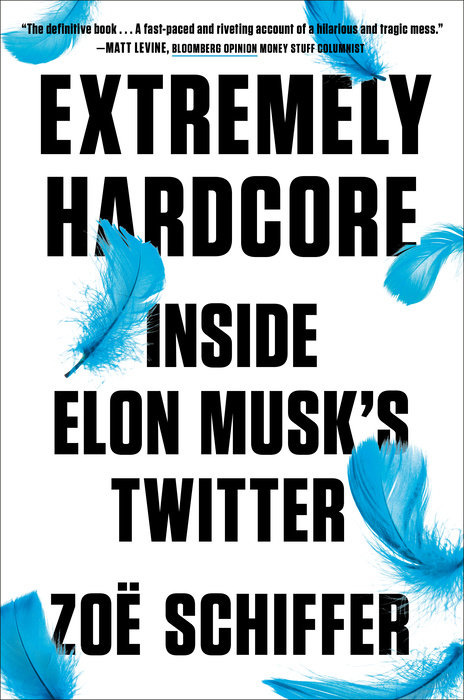

Zoë Schiffer (2024). Extremely Hardcore: Inside Elon Musk's Twitter. Portfolio. 330 pp.

We all live in Elon Musk’s world now—and as Zoë Schiffer shows in this meticulously researched book on Musk’s 2022 Twitter takeover, it is a bizarre, dysfunctional, and despotic world.

After reading Extremely Hardcore (Musk’s phrase describing the work culture he expected at Twitter), it is extremely difficult to maintain the illusion that Musk is some kind of business genius: Musk spent $44 billion to acquire a company worth only around $25 billion, effectively overpaying $19 billion, or the gross domestic product of a small country. Moreover, Musk has failed to turn Twitter/X into a profitable venture despite a ruthless slash-and-downsize program of corporate austerity. How, then, to make sense of the contrast between the outward myth of genius and the interior corporate dysfunction? Schiffer’s eminently readable blow-by-blow account of Musk’s Twitter acquisition raises the question: Is the world’s richest man still a rational decision-maker?

Schiffer’s book excels at bringing together the loose strands of the Twitter/X acquisition and its aftermath. Schiffer shows how Musk’s management strategy is essentially tyrannical, part-Logan Roy of HBO’s Succession, part-Stalin’s court, mixed with a heavy dollop of social awkwardness. In one episode described by Schiffer, a cost-cutting exercise with around forty department heads who were called in for a face-to-face meeting with Musk ended with one head fired for daring to express disagreement:

‘We were ready to show how hardcore we are,’ said one attendee. The group spent the day going through the budget line by line. After one woman tried to argue for an item that Musk did not find necessary, he fired her on the spot. ‘You can be wrong, but don’t be confidently wrong,’ he warned the group.

In another episode, after noticing that engagement with his posts was dropping, Musk demanded to know what was wrong with Twitter’s algorithm. An engineer, Yang, explained that the root cause was Musk’s own downward-trending popularity as a public figure: “He called the issue a “popularity drop” and pulled up the Google Trends graph, showing Musk the jagged downward slope that mirrored his decline on the platform.” Here’s Schiffer’s account of the aftermath:

Musk’s hands were starting to shake. Yang didn’t notice, but [another engineer, Randall] Lin did—he was watching Musk closely and saw the crash coming from a mile away. Shut up, man, he wanted to yell. Just stop talking.

When Yang finally did stop talking, Musk fired him on the spot.

In some ways, of course, there’s no mystery to Musk: He’s just a ruthless manager and capitalist owner rolled into one. He went into Twitter trying to cut costs down to the bone: “The fact that Twitter had a contract in place was not a good enough reason to keep paying. Musk said the only place that made Tesla sign paperwork was the DMV and urged people to try to negotiate every deal down by at least 75 percent.” Cut, cut, cut: This was the “secret” formula Musk brought with him into Twitter’s San Francisco headquarters. This owner/manager role is an unusual combination in today’s world of distant, hands-off owners who have outsourced day-to-day operations to a professional managerial class. Musk’s formula of what we might call charismatic accumulation hinges on the bravado of extreme wealth combined with ascetic discipline (of self) and ruthless tyrannizing (of others). So far this formula has worked reasonably well with Tesla and SpaceX. But has the formula run out of steam?

Buying Global Influence

Measured in purely business terms, the Twitter deal does look like a failure. The company was never very lucrative, even before Musk’s purchase. Over a decade, it only turned a profit twice, and in the two years pre-Musk’s takeover, Twitter lost around $1.3 billion in total. Musk took this less-than-stellar company, paid almost twice what it was worth, fired a huge chunk of its talent base, and pulled the platform rightward. Musk’s moves have caused thousands of intellectuals and media workers to flee for bluer skies and threaten to deepen X’s identity as a weird “alt-tech” social media platform, like Truth Social or Parler, rather than a more capacious global marketplace of ideas. As Schiffer shows, all of Musk’s attempts at instituting a subscriber-payments model or stopping the hemorrhaging advertising revenue losses have largely failed.

What if the loss-making Twitter deal was really aimed at paving the way for political influence?

But what if monetary profit was never the point? Before the 2024 U.S. presidential elections, Musk reached 200 million followers on X, and much of Schiffer’s book details how Musk pushed and prodded X engineers to rework the algorithm to favor his account. What if the loss-making Twitter deal was really aimed at paving the way for political influence? Despite the conspicuously negative business side of the 2022 acquisition, Musk’s political power and global influence have never been greater. He is now in many ways Trump’s right-hand man, appearing alongside the incoming second-term president-elect in numerous private settings, from transition planning in Mar-a-Lago to rocket-gazing in Brownsville, Texas. Alongside Vivek Ramaswamy, Musk has been promised a chance to run the upcoming Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE, threatening to turn Ayn Randian principles of minimal government into White House policy.

What Musk bought with his $44 billion was not so much a middling social-media business: As Schiffer points out, Musk could have built a Twitter clone at a far lower cost, like Mark Zuckerberg’s Meta did with Threads. Instead, Musk bought friends and influence in the highest of places. X may be a spiraling business, but it is still an effective megaphone. Musk may even have helped swing the vote for Trump, even as we should be wary of reductive accounts of election outcomes, which are shaped by multiple levers of causality.

Still, what Musk bought in 2022 wasn’t yet another company for his portfolio: He has plenty of those, from Neuralink to SpaceX and Tesla. Instead, Musk bought political power and the chance to help steer the world in his preferred direction. When you’re the richest man in the world, what remains are all the kingdoms of the world and their glory. You might just be able to put a price tag on that—a $44 billion price tag.

Theory Links (Nov. 2024)

Some of the things we’re reading, watching, and thinking about this month:

•Foreign Affairs: War and Peace in the Age of Artificial Intelligence

•Journal of the History of Ideas Blog: Marx and Republicanism: An Interview with Bruno Leipold

•Tim Barker, Sidecar/New Left Review: Dealignment

•AP: Top war-crimes court issues arrest warrants for Netanyahu and others in Israel-Hamas fighting

•The Guardian: More than 80,000 at risk of deportation from Australia under Labor bill likened to UK’s failed Rwanda plan

•The Economist: Why crypto mania is reaching new heights

•CNN: A shadow ‘financial crisis’ has cost the world $2 trillion

•London Review of Books: What else actually is there? [On Gillian Rose’s Love’s Work]

•A Night at the Garden: A 7-minute documentary about the 1939 pro-Nazi rally in Madison Square Garden.

I’m no economist, but I think that in a kleptocracy, “profit” should not be measured in purely monetary terms, as if the economic game were independent of the political game. Agents do not simply maximize revenue over cost measured in dollars, but maximize “revenue” (including potential power influence) over “cost” (not just monetary losses but losses in power and influence).