Lemkin's Concept of Genocide

A 1945 letter from jurist Raphael Lemkin takes us back to a historical moment when the concept of genocide was just beginning to take hold.

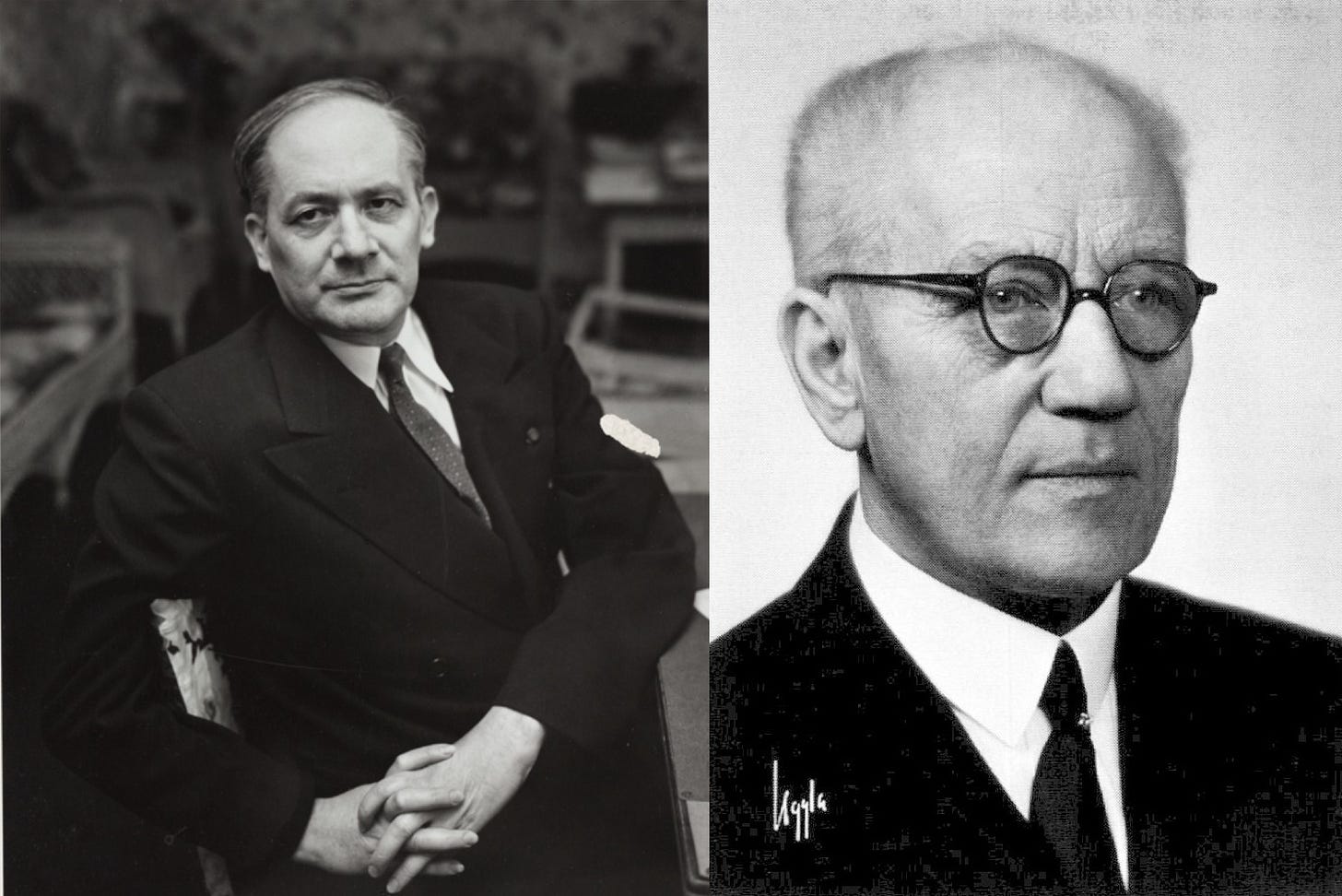

Some years ago, I was conducting research on the history of imprisonment in the Scandinavian countries, which later came to form part of my doctoral dissertation. One strand of this research took me to the Swedish National Archives in Stockholm where I came upon a series of boxes the containing the files of Karl Schlyter, Sweden’s progressive minister of justice in the mid-1930s. Schlyter had been something of a firebrand social democrat. His professional pedigree was impeccable, but unlike most bourgeois jurists, he had used his legal capital in service of a progressive reform of law and punishment—as seen in his advocacy for “emptying the prisons,” a radical stance for a highly placed former civil servant, judge, and then Minister of Justice.

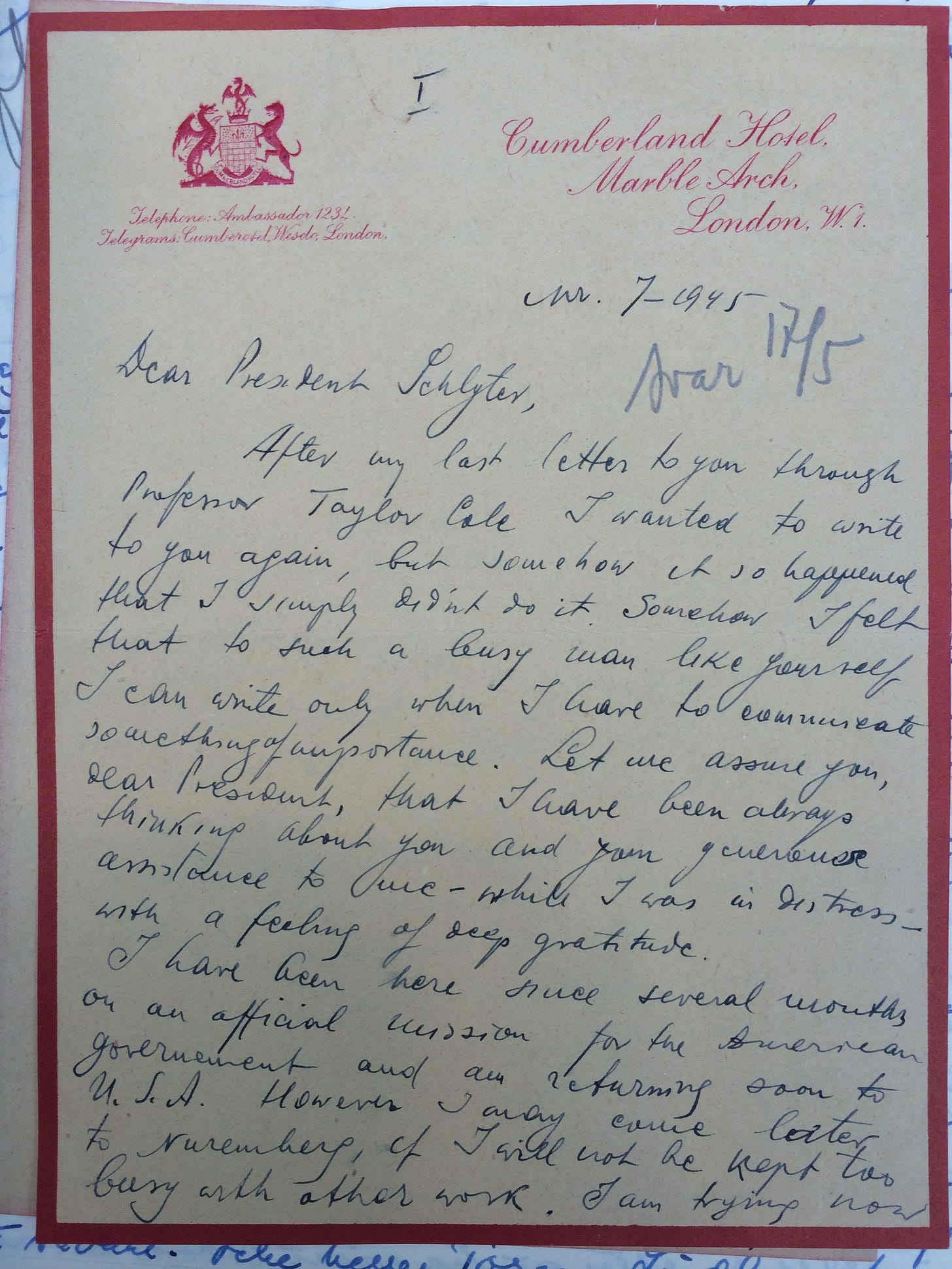

In Schlyter’s files, I came across a letter from Raphael Lemkin, the Polish-Jewish jurist who famously coined the term genocide. The letter is postmarked July 1945, mere months after the Allies’ victory over Nazism and fascism in Europe. Lemkin recounts that he is in the process of firming up the concept of genocide, a term he had first developed in his 1944 book, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe:

By ‘genocide’ we mean the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group. […] Generally speaking, genocide does not necessarily mean the immediate destruction of a nation, except when accomplished by mass killings of all members of a nation. It is intended rather to signify a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves.

In his 1945 letter, meanwhile, Lemkin writes, “I coined the word genocide from the greek genos - race, tribe” and the “Latin suffix ‘cide’ analogously to homicide, fratricide.” He writes that he would like to “propose to create from genocide a delictum iuris gentium,” or violation of international law. In this letter, we find Lemkin in the midst of his efforts to gain recognition for this still-nascent term.

Of course, the letter is not some grand juridical or theoretical statement, but a piece of correspondence between colleagues whose interactions had been interrupted by war. Schlyter had helped bring Lemkin to Stockholm in 1940; it was Schlyter who, “through his invitation and guarantee that Lemkin would not burden Swedish society financially, made it possible for Lemkin to obtain a visa and entry,” as a Swedish legal scholar noted in a 2016 essay. “But even in neutral Sweden, Lemkin did not feel safe,” another legal historian writes, and Lemkin left for the United States the next year, having secured a position at Duke University.

There is a kind of interwar nostalgia in Lemkin’s letter (“Coming back to old days and old friends…”), and he reminisces about the Bureau International pour l'unification du droit penal, an organization working for penal reform whose ambitions had been shattered by the rise of fascism, Nazism, and global war. He wonders whether genocide as legal concept will gain ground through the findings of the postwar Nuremberg Tribunal. In particular, Lemkin hopes that the French judge Donnediue de Vabres “will support the conception of genocide” and thinks that “[i]f the court accepts genocide as a charge it would be easier later to put it through an international treaty.”

In the event, the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg did use the “term ‘genocide’ to describe the fate of Jews and others under Nazi rule but did not charge the defendants with it as a specific crime.” It was not until December 9, 1948 that the United Nations established the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

Below is a transcription and facsimile of Lemkin’s letter. As we consider the horrors of genocide in our own times, including the ongoing genocide in Gaza, let us turn to the historical moment in which the term was on the cusp of coming into being as a realizable legal notion. The historical genesis of the concept, now more or less taken for granted —though still contested in applicability by some actors—reminds us of that essential fact about the law, and perhaps especially international law: that it is a field of struggle over the meaning of social and historical reality, including crimes of the gravest nature. Lemkin himself was a Holocaust survivor: “Only his brother, his brother’s wife and their two children survived the war years. At least 49 other family members perished.” If we live in a world that recognizes the legal category of genocide, it is thanks in large measure to the efforts of one scholar—and survivor—of those very crimes.

[Letter from Raphael Lemkin to Karl Schlyter]

Cumberland Hotel

Marble Arch

London W.1.

7 - 1945

Dear President Schlyter,

After my last letter to you through Professor Taylor Cole I wanted to write to you again, but somehow it so happened that I simply didn’t do it. Somehow I felt that to such a busy man like yourself I can write only when I have to communicate something of importance. Let me assure you, dear President, that I have been always thinking about you and your generous assistance to me - while I was in distress - with a feeling of deep gratitude.

I have been here [in London] since several months on an official mission for the American government and am returning soon to U.S.A. However I may come later, to Nuremberg, if I will not be kept too busy with other work. I am trying now to send you my volume Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, published by Carnegie Endowment for international peace. Chapter IX on genocide - destruction of nations - has drawn certain attention in America and England. I coined the word genocide from the greek genos - race, tribe [-] and the Latin suffix “cide” analogously to homicide, fratricide and I do propose to create from genocide a delictum iuris gentium. Of course an international treaty would be necessary for that. In time of war genocide can be punished through the instrumentality of the Hague Convention, but for time of peace one needs a treaty, specially for purposes of universal repression and eventually extradition in some cases. Since you did so much for international criminal law and international juridical collaboration I would be more than happy if I could have your approval of this idea. I wish we could have again our Bureau International pour l'unification du droit penal. It would be easier to put it through, since the internationalisation of genocide is only a further development of my proposals made in my report on terrorism at the Madrid Conference of our Bureau.

I am very glad that Donnediue de Vabres is on the court. I hope he will support the conception of genocide, while it is included in the indictment. If the court accepts genocide as a charge it would be easier later to put it through an international treaty. The support of men of your humanitarian enthusiasm and high prestige in the world, which you enjoy, would be invaluable to the making and enforcement of such a treaty.

Coming back to old days and old friends. I wanted to tell you that Professor Rappaport survived and he is now again judge on the Supreme Court of Poland in the city of Lodz. I know you will be happy to hear that.

I hope you are well and I am sure that your very important legal activities are giving you great satisfaction. I will be more than happy to hear from you either here in London or in U.S.A. My recent private address in America is:

Dorchester House, Aptm. 627, 16 Street, Washington D. C.

My official address: War Department, War Crimes Office, Washington D. C. - Munitions Bldg.

Let me tell you how happy I am about the successful developments in your splendid country, for which I guard a feeling of great admiration. And let me send you my best warm regards.

Sincerely yours

R. Lemkin

Facsimile of Lemkin’s letter to Schlyter

Dr. Victor L. Shammas is Head of Department and Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology and Social Work, University of Agder in Norway. He holds a PhD in Sociology from the University of Oslo (2017) and has previously worked as Senior Researcher at the Work Research Institute (AFI), Oslo Metropolitan University. His work has appeared in journals such as Constellations, Punishment & Society, Critical Criminology, Capital & Class, and the British Journal of Criminology.