Norway's Right is Obsessed With Immigration and Crime

Norway is a safe, prosperous, and diverse society. So why can't the right stop talking about immigration and crime?

It’s election season in Norway. On September 8, voters will likely choose between a red-green coalition—including the Labour Party, Socialist Left Party, Red Party, Green Party, and Centre Party—or a right-wing bloc, potentially led by the ethnonationalist-neoliberal Progress Party, currently polling second behind Labour, and joined by the Conservative Party, Christian Democratic Party, and Liberal Party.

With less than two weeks to go, some polling indicates the red-green bloc may secure a majority in the Storting. But it remains a tight race. August polling averages, for instance, show the red-green coalition with 85 mandates, a narrow majority, against the right-wing bloc’s 84 mandates.

And this is assuming all parties on the red-green side manage to come to an agreement. One local member of the traditionally red-green-supporting Centre Party recently argued that the party should switch allegiances, even though similar pleas from the Conservatives were rejected by the Centre Party’s leader earlier this year. The smaller parties on both sides of the political spectrum will also play a pivotal role—in Norway, parties that clear a 4 percent threshold can compete for bonus seats in parliament. There’s a lot at stake whether the Green Party, Christian Democratic Party, and Liberal Party manage to clear the hurdle, as they could make or break their respective side’s majority.

The Progress Party has also made significant gains since the previous parliamentary elections in 2021; some of their gains have been offset by the Conservative Party’s waning popularity. Still, the Progress Party’s views on immigration have in many ways set the tone and tenor for the entire election.

Despite some positive recent polls suggesting a red-green majority is within reach, then, the end result is far from certain. The race is neck-and-neck. As ever, the final outcome will be determined by the voters, but also a good deal of political horse-trading.

The Right’s Weaponization of Immigration and Crime

The right has been remarkably successful at taking charge of the public conversation and drilling down into two key themes: immigration and crime.

Throughout the election season, the Conservative Party has run social media ads advocating “tightening immigration” and, borrowing from the populist right’s playbook, has pushed a mock-ironic anti-immigration slogan: “No slogans. Just less immigration.”

The Progress Party in particular has worked hard to link crime and immigration in the public mind, and it has been remarkably successful at drawing the discourse in its preferred direction.

For a full year leading up to the election, the Progress Party’s leader, Sylvi Listhaug, has hammered on her party’s signature theme: opposition to immigration. “If immigration is not dramatically slowed down now,” she said in November, “we risk that in a few years we will not be able to afford to take care of our own citizens.” Listhaug—a kind of Nordicized Trump or Meloni of the North—has worked indefatigably to portray crime as a widespread and growing social problem, rooted in immigration and centered on young, urban (ethnic-minority) men.

The fact that both the Progress Party and the Conservative Party have been able to do so, almost unimpeded, is peculiar, given the fact that Norway remains one of the safest countries in the world. If anything, immigration is in many ways the solution to some of Norway’s problems, including a looming demographic crisis—an aging population amidst declining birthrates—and potential labor shortages, especially in the country’s welfare state.

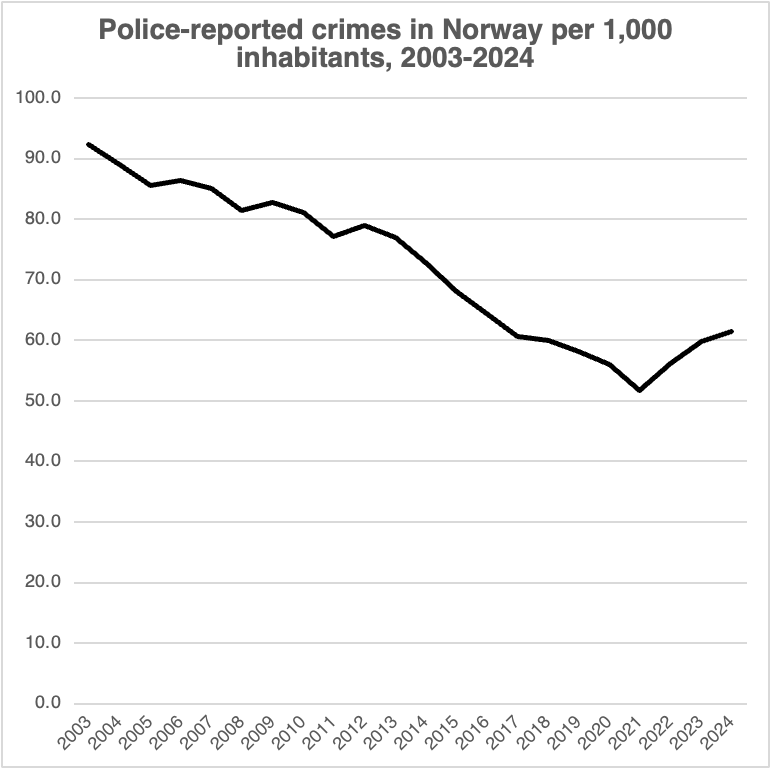

The manufactured nature of the crime issue is only compounded by the fact that Norway’s overall crime rate has declined steadily over the last few decades. Since the early 2000s, the rate of police-reported crimes (shown below) has dropped by nearly a third from over 90 crimes per 1,000 inhabitants to just above 60 crimes per 1,000 by 2024. There are categories of crime that are an exception, such as a moderate uptick in police-reported violence—from 6.9 cases per 1,000 in 2003 to 8.2 cases in 2024—but crime in general is trending downward, and the slight uptick in specific categories hardly warrants the kind of bombastic societal discourse the Norwegian right has been pushing.

Interestingly, this great Norwegian crime decline has coincided with a significant expansion in immigration. Some may be surprised to learn that Norway has become a diverse, multicultural society. The idea of a nation of blonde, blue-eyed Vikings is a tourist stereotype—or an ethnonationalist fantasy cultivated by the far right. In the capital, Oslo, immigrants and their descendants make up more than a third of the population; in the country as a whole, these groups make up more than 20 percent of the population. Immigrants have enriched Norway.

But if immigration has gone up while crime has fallen, the supposedly tight connection between crime and immigration that the Norwegian right insists upon is clearly a misrepresentation of macro trends. As one Norwegian sociologist observed earlier this year, “In 2023, almost 100,000 fewer crimes were reported [in Norway] than in 2003, a reduction of 22 percent. During the same period, the number of immigrants and Norwegian-born people with an immigrant background increased by 227 percent.” It’s an unpleasant fact that right-wing politicians are rarely, if ever, forced to confront: how do they make sense of the fact that Norway has become an increasingly diverse society—while crime has declined over the long run?

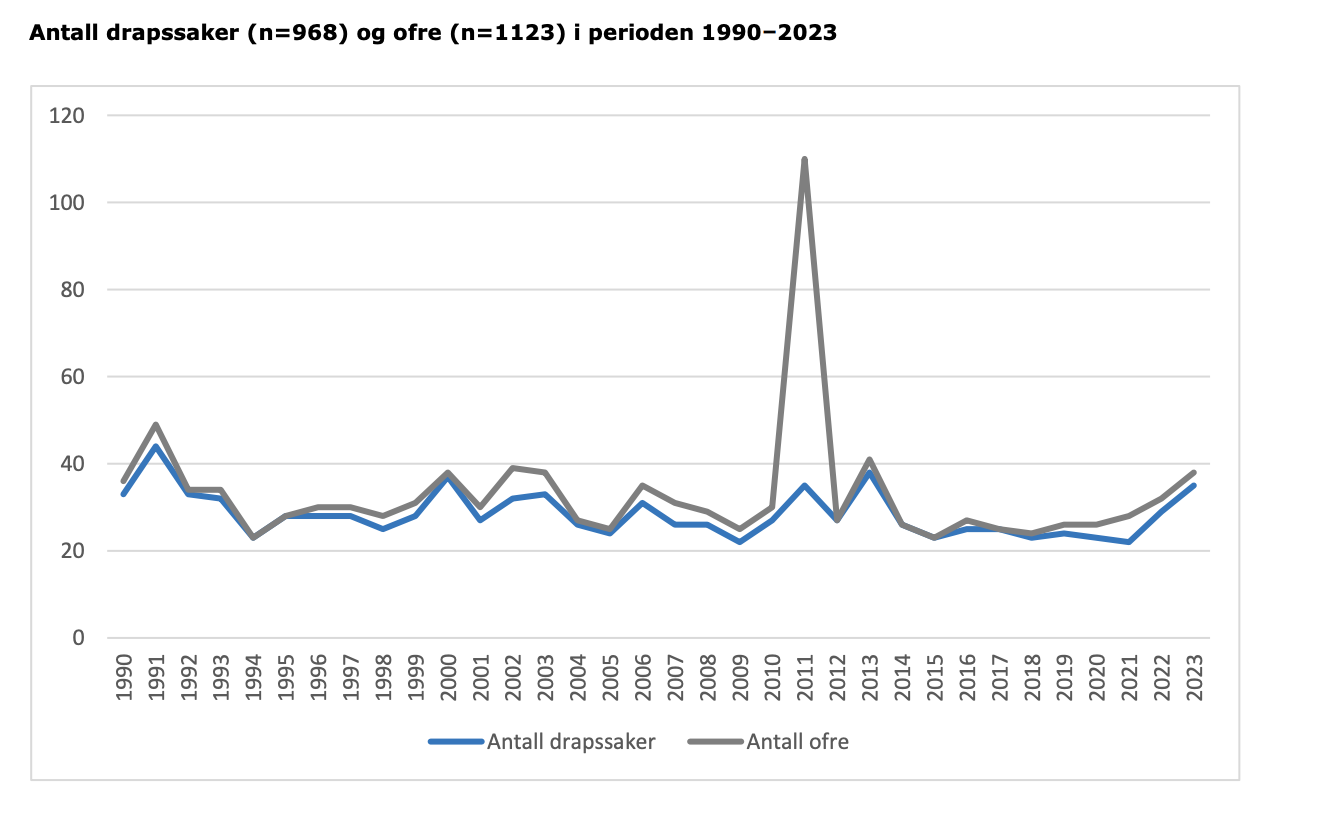

One potent measure of how safe Norway remains can be found in the country’s homicide statistics. The absolute number of homicides has remained stable since the 1990s, hovering at around 30-40 victims per year; in the same period, the population grew, meaning that the per-capita homicide rate in reality declined over the period. Norway’s homicide level is far lower than that of the United States, England, and even neighboring Sweden.

As the chart above shows, the only exception to this trend lies in a single year, 2011, when a right-wing extremist, Anders Behring Breivik—a one-time member of the Progress Party—killed 77 people, including 69 people at a progressive youth summer camp outside Oslo, and a further eight individuals in a bombing of government buildings in downtown Oslo. With the exception of the 22 July, 2011 attacks, perpetrated by an Islamophobic, white-supremacist mass murderer, Norway has been remarkably successful in ensuring public safety and relatively low levels of crime.

Of course, when the right speaks of threats to public safety, they generally mean street crimes—such as muggings and robberies—or other disruptions of public order. The Norwegian right also tries to tap into broader feelings of uncertainty and insecurity, often related to ethnocultural anxieties about the disruption of traditional folkways.

This is not to minimize the impact that crimes, or the threat of crime, can have on people’s welfare. But the right-wing framing of crime has been disproportionate to its true incidence—and it has clearly been ethnicized, aimed at activating the basest nativist sentiments in the population.

It’s hardly surprising that Norway has remained a safe, thriving, and prosperous country: its Switzerland-like levels of oil-fueled wealth, combined with plentiful government spending on social security and public welfare, have allowed many to enjoy a sound living standard. It would be peculiar if such a prosperous country were to engender high levels of social pathology.

That makes the right’s narrative all the more unreal and fantastical. Unlike in other countries, where “native” locals may feel their jobs are being “taken” by immigrant arrivals, there is no evidence that immigration is causing economic dislocation in Norway. Quite the contrary: immigrants often fill positions for which there are no takers.

The Death of Tamima

With just over two weeks until the election, Norwegians were once again reminded of the threat of right-wing extremism to public safety. A 34-year-old Ethiopian-Norwegian social worker, Tamima Nibras Juhar, was murdered in her Oslo workplace, a child welfare institution, by a young man with far-right views.

While the public condemnation of the murder was swift, most commentators and politicians failed, at least in the initial aftermath, to situate it in its proper sociological context: increasingly virulent anti-immigrant rhetoric from right-wing politicians, combined with the far right’s growing self-assertiveness.

A week prior to the attack, a radical far-right party, the Norway Democrats (ND), had organized a so-called “remigration conference”—one of the most high-profile events for far-right activists the country had seen in years. Among the participants were the German Alternative für Deutschland politician Lena Kotré and the French far-right ideologue Renaud Camus, originator of the white-nationalist, conspiratorial notion of a “Great Replacement.”

The week following, a former (respected) correspondent for Norway’s public broadcasting corporation, Anders Magnus, penned an op-ed in the newspaper Aftenposten claiming that “the welfare state [is] threatened, primarily due to immigration from clan-based, Islamic countries in the Middle East, Africa and Asia”—an unsubstantiated and deeply Islamophobic claim.

More broadly, both the Progress Party and Conservative Party had repeatedly beat the drums of nativism—against immigrants.

The murder of Tamima brought home what was really at stake this election season in Norway: the imperative need to protect an increasingly diverse, high-functioning society threatened by racism, xenophobia, and nativism. This toxic triad had claimed 77 lives on July 22, 2011, and another life just a little over two weeks before the election. How many more lives would be lost before Norwegians realized that immigration wasn’t the threat, but rather those seeking to cultivate fear and hatred of diversity?

Neoliberalism, Fascism, Climate Change—and Gaza

Any major election will of course cover a range of additional issues.

One might have expected the election to hinge on a few of the key political questions of our time—say, the threat of fascism and destabilization spreading from Trump’s White House to Europe at large, with offshoots of growing far-right sentiment seen in Germany’s rising AfD and France’s National Rally, Nigel Farage’s Reform UK, or—in Norway’s next-door neighbor—the Sweden Democrats. Or, after an unusually sweltering Nordic summer, one might have expected more attention to the growing threat of catastrophic climate change, with an urgent need to decarbonize an economy heavily reliant on fossil fuel exports.

Neoliberalism—along with its proponents and discontents—has not been entirely absent. The Conservatives and Liberals have been focused on the wealth tax, which they claim forces rich Norwegian business owners to drain their companies of capital to pay their tax bill. The left has repeatedly pointed out the exaggerations and outright false reporting on the issue. The Red Party has attacked the growing prevalence of private health insurance in a country that has prided itself on its public healthcare system. The Socialist Left Party has focused on rising food prices and widening social inequalities.

On the threat of the far right, and Trump more specifically, Norway’s Labour government has—like most of Europe—found itself taking a “pragmatic” stance. The government has drawn on the political capital of former NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg, brought into government as Minister of Finance earlier this year—to secure (seemingly) a modicum of concessions from Trump 2.0 on trade and tariffs.

But across the party landscape, with the exception of the radical left, there has been disconcertingly little willingness to draw a connecting line between Trump’s authoritarianism and outright fascism to analogous ideological tendencies at home—or in Europe, more broadly.

On climate change, too, the election has been decidedly muted: unimpeded oil and natural gas exports are widely seen as a necessary contribution to European energy independence. In one telling moment earlier this month, the Progress Party’s Listhaug said the climate activist Greta Thunberg, who had been protesting against the Norwegian oil industry, “should be deported from the country” —an echo of Trump’s MAGA rhetoric.

At one point, the election looked set to become about Gaza. Earlier in the summer, a Norwegian group of academics calling itself Historians for Palestine released a report detailing the country’s significant investments in Israeli companies—including companies linked to occupation and genocide—through Norway’s $2 trillion “Oil Fund,” the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund. The report was resoundingly ignored.

But it wasn’t until mid-August when Aftenposten covered some of the same material on its front page that the story exploded. The fund, it turned out, had outsourced some of its investment decisions to several Israeli portfolio managers, some with links to the Netanyahu government. The Labour Party-led government swung into action, selling off a sizable part of its Israel-linked holdings. Heading off a bloodletting to the left by appearing resolute on Israeli investments, and a hemorrhaging to the right by maintaining its pro-business credentials, the Labour Party government weathered the storm, mere weeks before the election, by striking a balance between ethical claims and studied financial neutrality.

A High-Stakes Election

Many Norwegians still think of Norway as a society and country somehow set apart from the rest of the world: exceptionalism remains a powerful cultural idea. As one prime minister put it in the 1990s, “It’s typically Norwegian to be good”—a remarkably conceited statement.

Unfortunately, at the moment, there’s nothing exceptional about Norway’s politics. Across Europe, the right is on the rise. Nativism is a key rallying point. But the Norwegian right isn’t just threatening immigrants and minorities. It’s pushing along a wide front, from trying to roll back a key wealth tax to blocking the green transition. The Progress Party’s partners on the right increasingly look like willing dupes who may help bring to power a political force akin to Meloni, Trump, and Farage. That would be a disaster for Norway. Only a strong center-left coalition stands in the way of this becoming a reality. The stakes are high, and the race will be close.

Great piece!

Such paranoid fear of the Other is inextricable to being right wing and is perhaps a cause of it.