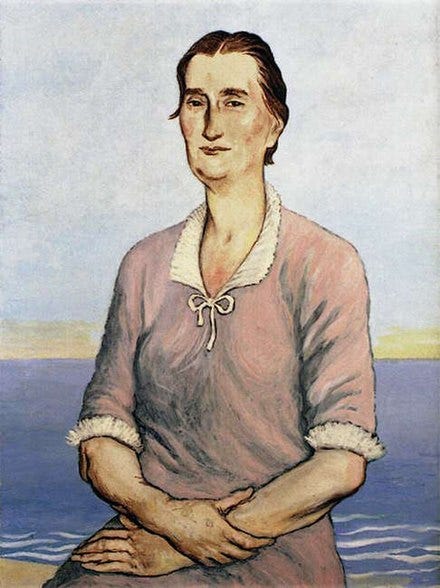

Proust's Housekeeper

Céleste Albaret invites us to share in the delight that a person like Marcel Proust, for all his strangeness, ever walked among us.

Céleste Albaret (2003). Monsieur Proust. New York Review of Books. (Foreword by André Aciman, translated from the French by Barbara Bray.)

Monsieur Proust is a remarkable socio-historical and literary document, offering a remarkably unvarnished account of a great literary personality’s everyday life. Anyone who cares about Marcel Proust’s writings should read Céleste Albaret’s gripping account of her years as his housekeeper. The book captures Proust’s peculiar, if not outright bizarre, life in Paris around the time of the Great War—which was also, of course, a time of frenzied creative activity, resulting in his monumental work, À la recherche du temps perdu.

But how could a book about the daily life of a writer’s housekeeper be gripping—even a very great writer and even an extraordinarily observant housekeeper? And yet gripping Monsieur Proust is. We follow both characters—for that is what they become in Albaret’s deft prose—along their varied stages of evolution, synthesis, and (spoiler alert) eventual disunion.

One quickly senses just how disturbed Proust’s interior life must have been: his irritation with every minor noise, whether from the neighbors or from Albaret’s own domestic work, his annoyance over his daily (nightly) coffee being insufficiently hot, and so on. Albaret notes that Proust had the uncanny ability to do without everyone—everyone except her, that is. He didn’t need anyone, it seemed to her, even if lots of people thought they were his friend, perhaps his most “inhuman” quality: “[H]e could do without all of them with the greatest of ease” (p. 223). But his unsociability, a kind of post-human quality, was in service of a deeply humanistic literary project: “Now I realize M. Proust's whole object, his whole great sacrifice for his work was to set himself outside time in order to rediscover it. When there is no more time, there is silence. He needed that silence in order to hear only the voices he wanted to hear, the voices that are in his books” (p. 50).

Albaret doesn’t gloss over Proust’s despotism nor does she completely forgive Proust’s prickly-pear qualities for serving the higher function of Art. Instead, Albaret is a subtle dialectician who realizes the fullness of her biographical subject, with all its multivalences, approaching what the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze would call “a life”: a life is just a life, to be described and accounted for, not destroyed—for it is up to us to make something out of every life we have a chance to learn about.

Proust was, famously, neurotic verging on the extreme. His own explanation for this was was that being a the son of a doctor, a certain hypochondria was unavoidable. “When you are a doctor's son, you see, you end up being a doctor yourself” (p. 60)—surely one of the great sociological defenses of neuroticism.

He was a nocturnal creature, going to bed in his cork-lined room at sunrise and rising only with the dusk. His physical needs seemed limited: “It isn't an exaggeration to say he ate virtually nothing,” Albaret writes, of what we today would probably describe as an eating disorder. “I’ve never heard of anyone else living off two bowls of café au lait and two croissants a day. And sometimes only one croissant!”. But Albaret doesn’t shy away from a brutally honest catalogue of his tyrannies, major and minor; still, we get the sense that there existed a profound bond of love between them, and she became far more than a domestic servant to him.

Above all, there is a tremendous sense of decency, even decorum, throughout her account, but also a genuine, authentic love: almost a divine love, totally innocent. At first an inexperienced young woman from the countryside, recently moved to the bustling metropolis of Paris, Albaret had to be taught everything about housekeeping, Albaret later becomes something like a maternal surrogate to Proust: “What was so marvelous was that with him there were moments when I felt I was his mother, and others when I felt I was his child” (p. 90). There’s plenty to be aggravated about here, of course, but, importantly, Albaret herself largely isn’t. Instead, she seems grateful to have played a not-inconsiderable part in the life of her beloved “Monsieur Proust,” delighting in his books, their reception, and his standing in literary history.

So was Albaret just a victim of ideology—the beliefs about masters and servants obtaining in a fin-de-siècle European society and stretching into the interwar years, where servitude and domination were sentimentalized, and servants were enjoined to love their masters, all for the purposes of securing consent to social domination? The ironclad hierarchies of class and privilege hang over nearly every page of Monsieur Proust; but this seems almost too obvious to mention, and what is remarkable is that Albaret—who by the time she came to write her memoirs was looking back on her youthful labors from the perspective of old age and considerable experience—doesn’t seem at all troubled by the brute facts of class and gender so vividly on display in these pages.

Instead, one gets the sense that, in the end, she took more from Proust than he took from her. His was an extraordinary tutelage, it seems, and Céleste Albaret invites us to share in her gratitude that such a strange, disorienting, sensitive, and extraordinary personality ever walked among us.

Many thanks for this. I thought I knew this NY Review Books series well, but this book got by me. I'll find myself a copy. Anyone with an interest in Proust should know about the Proust page at Reddit:

https://www.reddit.com/r/Proust/