The Dangers of TACO

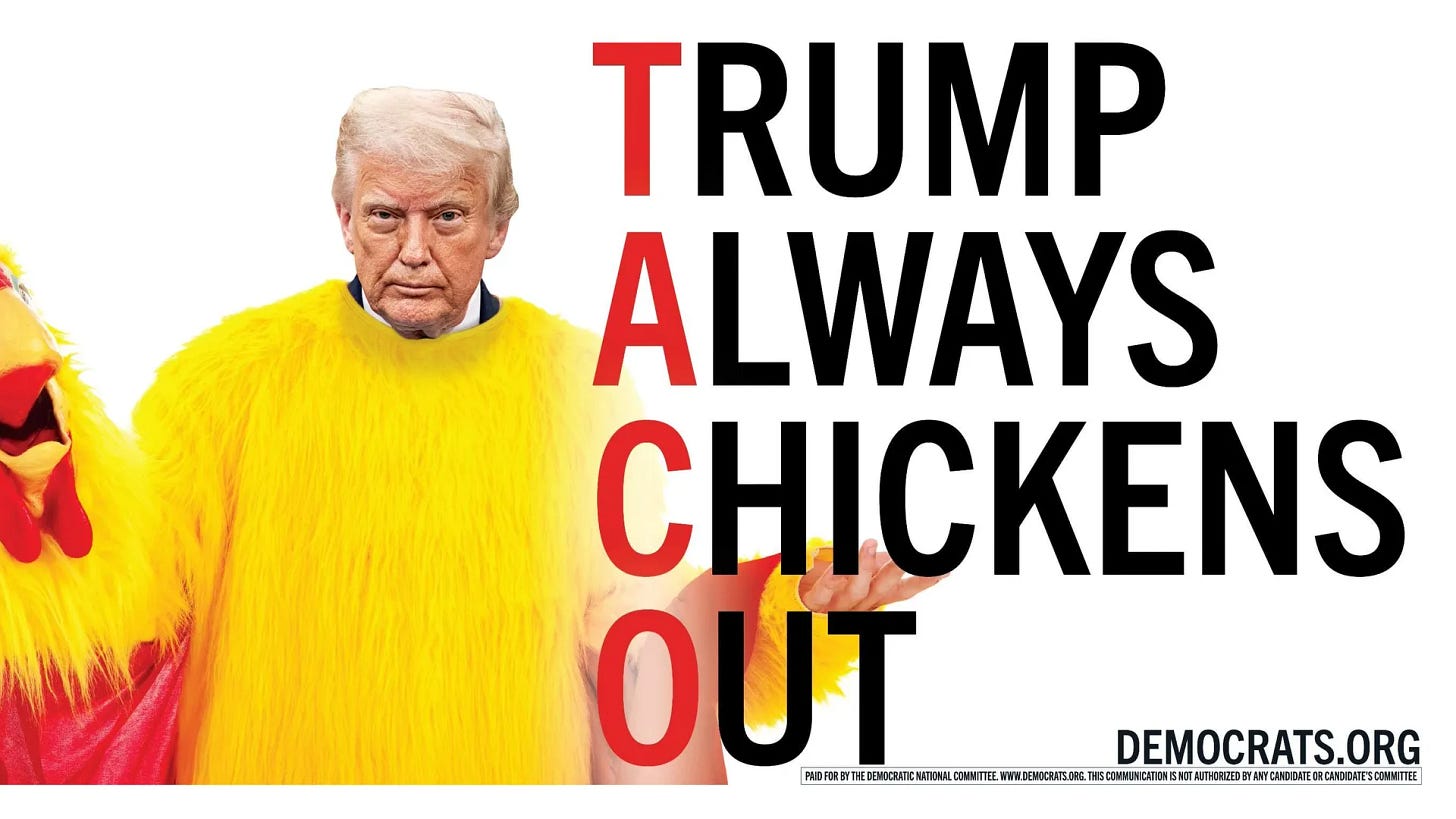

Trump Always Chickens Out, or TACO, was a playful way of criticizing Trump's early second-term policies. But goading Trump into taking a firmer stance is a risky move.

At first glance, TACO, or “Trump Always Chickens Out,” seemed like a smart, playful acronym when it first began making the rounds on social media earlier this year. In the wake of Trump’s apparent vacillation over global tariffs, TACO named a feature of Trump 2.0’s first few months: While “reciprocal” tariffs were announced on April 2nd to much fanfare, they were shortly thereafter paused for a number of countries, suggestive of a Trump White House once again in disarray despite the post-2024 election propaganda about a more professional and polished second-term Trump. Trump 2.0 was still, it seemed, characterized by brash pronouncements one moment, followed by the inevitable climb-down the next, as markets were roiled by MAGA shock therapy. In a piece published weeks before the Iran strikes, the FT’s Gideon Rachman has also drawn attention to a study showing that Trump has threatened dozens of adversaries with the use of force, but "only" deployed force a handful of times. Hence, TACO: Trump always backs down, chickens out, doesn’t have the guts to stay the course.

In one sense, of course, TACO seemed to hit Trump where it hurt. Like all far-right authoritarians, Trump values strength—or a particular conventional understanding of strength—above all else. To call him weak seemed like a form of resistance to Trump’s toxic brand of politics. And he didn’t like it. “I chicken out? I’ve never heard that,” he said in a late May press meeting in the Oval Office. “Don’t ever say what you said,” he told one reporter. “That’s a nasty question. To me, that’s the nastiest question.” TACO held him to account by his own standards: You may say you’re strong, but when push comes to shove you’re actually quite weak—you chicken out.

In this sense, it was a always a somewhat peculiar criticism, especially coming from the left: The problem with Trump, TACO implied, was not the content of Trump’s politics but rather his own failure to live up to his promises—that is, not delivering the content of his politics fully enough. In other words, it was an attack on Trump’s hypocrisy rather than on the substance of Trump’s politics.

But this is always a risky maneuver for critics to undertake, because it’s a criticism that can be addressed by implementing policies these critics likely disagree with. With TACO in hand, we might ask: Do we really want a non-hypocritical fascist authoritarian in power? On the contrary, one might say: The only thing worse than a two-faced right-wing authoritarian is a right-wing authoritarian who does exactly what they promised they would do.

Chickening Out—or Doubling Down?

Another way of thinking about this is to say that TACO is a form of immanent critique, as the Frankfurt School might have put it, a criticism that operates on the terrain of the enemy, so to speak, deploying the adversary’s own criteria to denounce or oppose them. This can be a strategically smart move under a narrow set of political circumstances—when one’s opponents are on the cusp of having their hegemony dismantled, say, or at least fundamentally weakened; that is, when there are just enough supporters of the old order who are on the brink of turning against the old ways, and yet who are, intellectually and ideologically, still wedded to the old order’s ways of thinking. Under these narrow conditions, using the ideas and language of the old order against it might push unsure supporters over the top and bring them to one’s own side.

But immanent critique risks backfiring in a situation where one’s opponent enjoys near-total hegemonic dominance—arguably the case with Trump 2.0. Yes, there are signs of a budding oppositional social movement (the “No Kings” protests brought around five million people out into the streets across the U.S.), but the organized political opposition, the Democratic Party’s net unfavorability has actually grown under Trump’s first five months in power—a staggering feat given the extremism of Trump 2.0—and its leadership is characterized more by a failure to criticize the Trump White House than of rising to the occasion (with a few notable exceptions, mainly from scattered elected representatives than the leadership as such).

When there is no credible, high-functioning, well-organized political opposition, immanent critique only risks goading the powers that be into doubling down. And that is precisely what TACO threatens to accomplish in the present moment—to the extent that it plays a formative role in the discursive landscape at all. Since Trump hates being called weak, he is likely to respond to TACO, and relatedly patterned responses, with what we might call “TADD”: Trump Always Doubles Down. Or, going further, TADWHW: Trump Always Does What He Wants—admittedly more of a mouthful than the elegance of TACO.

Revalorizing Politics

TACO is not a formula that tries to fundamentally shift the terms of debate. But if we look back through history, there are plenty of movements that have. Think about the history of early Christianity, when the apostle Paul faced off the strength-worshipping Roman Empire: As he journeyed around the Mediterranean to cement a semi-subterranean network of early communities of believers, he penned letters to his communities where he laid out his religious, but also organizational and even political, vision.

In one famous passage, Paul tries to upend the ancient world’s ethical order by announcing, brashly: “For when I am weak, then I am strong”—an almost delusional statement that flew in the face of the might-makes-right paradigm governing the ancient world. “I will boast all the more gladly about my weaknesses,” Paul writes in the same passage. “I delight in weaknesses, in insults, in hardships, in persecutions, in difficulties.” Within the context of antiquity, this must have seemed deeply strange, just as it remains puzzling and disconcerting even today, if we take in the full weight of his words. Strength is weakness, weakness is strength, Paul proclaims—almost like a Zen koan. When the Roman Empire slaughters its enemies, this is actually a sign of their (ethical) weakness; when early Christ-believers are devoured by lions in the arena, this is actually a sign of their ethical steadfastness and, yes, strength.

Paul’s almost delirious statement—how can weakness be strength?—is an early example of the tactical deployment of revalorization, assigning new and counterintuitive, paradoxical, or inverted meanings to behaviors, ideas, and social phenomena. His was a theological motivation, of course, but we need not be detained by that part of the story. The broader political point is that any oppositional movement must, sooner or later, realize the inherent improbability of trying to win political struggles on the terrain of the adversary—certainly when that adversary is significantly more powerful.

By sociopolitical alchemy, revalorization turns a demerit into a merit. It upends the ethical-political order by throwing its terms up into the air and assigning new meanings. And it does so because it recognizes that this paradoxical, almost delusional move is the only way a fundamentally weak movement can ever really stand a chance against the powers of the world.

Raw Power—and Its Discontents

What would a revalorizing approach to Trump look like, then? It would state that the problem with Trump isn’t so much that he “chickens out”—lighthearted and amusing as that image is, of course, especially to those tired of his deeply destructive policies—but that, precisely, he doubles down, or—increasingly—does exactly what he wants. This is worse than chickening out, because it suggests a certain swaggering dominance by someone who knows the full weight of their power.

But in so doing, Trump thereby reveals his essential ethical weakness, which is the “weakness” betrayed by the conventional world in all its worship of raw strength and power—a world increasingly has come to prize might alone in all its conventional forms: military firepower, economic supremacy, dominion over both our fellow human beings and the natural world. Revalorizing politics in the age of Trump 2.0 means challenging its fundamental coordinates, up to and including superficial notions of strength and bravery, or conventional understandings of masculinity and power, which are part of the reason we find ourselves in this political situation in the first place.

* * *

When I was engaged in ethnographic field research on parole hearings in the California state prison system some years ago, one of the parole commissioners gave me a piece of advice: If someone ever threatens you with a gun, he said, never ever say, “What are you gonna do, shoot me?” Because they just might. He had seen—or heard—it happen too many times in the course of his career.

That exchange came back to me as I started thinking more closely about TACO: What are you going to do, President Trump—actually implement your stated policies? Well, he just might. Best not to goad him into it.

The problem with Trump isn't so much that he's a hypocrite—though he is that as well, especially with his former “antiwar” or isolationist posturing now rapidly being falsified—or that he lacks follow-through, but that he's busy doing exactly what he promised he'd do and much more besides. Trump’s supposed cowardice is the least of our problems. Better to focus our critical energies elsewhere.