The Specter of Inflation

The far right has weaponized inflation. We should critically examine how nationalist movements activate and manipulate ideas about economic hardship for political gain.

One frequently invoked explanation among progressives for the resurgence of far-right politics in recent times is inflation: Prices rise, food and energy costs go up, mortgages become more expensive, wages don’t keep up, and, so the story goes, as a consequence, working- and middle-class voters begin casting about for a scapegoat to blame for their economic woes. In short, economic pain pushes ordinary people into the arms of the radical right.

So too with Germany’s recent Bundestag elections in which the far-right party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) secured more than 20 percent of the vote. Only hours after polls closed, the economist Isabella Weber wrote on social media: “75% of AfD voters say they are very worried that prices are rising so much that they can’t pay their bills. Inflation once more fueled the extreme right.”

Weber had invoked the same explanation in accounting for Trump’s successful presidential bid a few months earlier: Two weeks after the 2024 U.S. presidential election, the economist claimed that inflation was “clearly the most important question for voters.” In an interview with French media, Weber reiterated that “Trump's election shows that inflation is a danger to democracy.”

She was not alone in making this claim. The morning after the November election, The Guardian’s economics editor Larry Elliott wrote an inflation-centered piece arguing that price increases had “helped secure [a] Trump win.” On Elliott’s view, “Trump insisted while campaigning that the economy was in poor shape, a message that resonated with many Americans unhappy about the increases in the cost of living during Joe Biden’s presidency.” Or as the Wall Street Journal’s chief economics commentator Greg Ip recently put it: “Nothing did more to deliver the White House to Donald Trump than inflation.”

It’s not (only) the economy

But while we shouldn’t deny the economic hardships that many ordinary Americans face, inflation-centered accounts of Trump’s return to the White House suffer from multiple flaws. First, the overall estimated 5.2% inflation rate under Biden’s presidency was hardly Biden’s fault alone; it was the predictable outcome of the trillions of dollars in necessary government spending on much-needed pandemic relief programs, but also the effects of pandemic-related supply-chain disruptions, energy and food price shocks from external causes like the Ukraine War, and the foreseeable result of a reopened world economy as the COVID-19 pandemic came to an end.

Second, and more importantly, inflation was largely under control by the time the 2024 election had arrived. By October 2024, the month before the election, the all-items price index had risen 2.6% over the last 12 months, hardly an earth-shattering level; and the 12-month percentage change of food prices in the U.S. stood at 2.1%, almost half of what had been the case in October 2020, the month prior to Biden’s defeat of Trump at the polls.

In 2024, U.S. voters had, of course, been through a period of high inflation under Biden, evidenced by the significant decline in real wages in the first half of his presidency; but by the end of 2024, real wages were back at their pre-pandemic levels.

In short, inflation wasn’t an “objective” reality that Trump could simply point to and allow to run its own course among the electorate. Instead, it was a constructed, spectral presence, which Trump skillfully repackaged along with other key elements of his politics, including anti-transgender attacks, nationalist nativism, and “culture-war” positioning, to snap up voters from the opposing side. As important as the “pure” economic effects of inflation may have been was the political activation of inflation as a weaponized signifier in the far-right’s battle against centrist neoliberalism. To claim that inflation was the “cause” of Trump’s rise, unadulterated by processes of communicative construction, would be to accept uncritically the far right’s own problem-diagnosis, falling prey to its propagandistic portrayals of social reality.

Again, this isn’t to say that ordinary people’s economic concerns shouldn’t be taken seriously nor that everything was rosy in the realm of the economy pre-November 2024. To take just one indicator: The top 10 percent of Americans controlled more than 70 percent of the country’s net wealth and nearly half of its pre-tax income in 2023, according to the World Income Database—an astonishing level of economic inequality that feeds into ongoing social pathologies. But even in the realm of “hard” economic inequalities, one could imagine a far-right movement tapping into and exploiting these differences for their own political gains; inequality is not in and of itself a “leftwing cause,” because it too can be weaponized by the right to devastating effect, as history has shown.

The German inflation conundrum

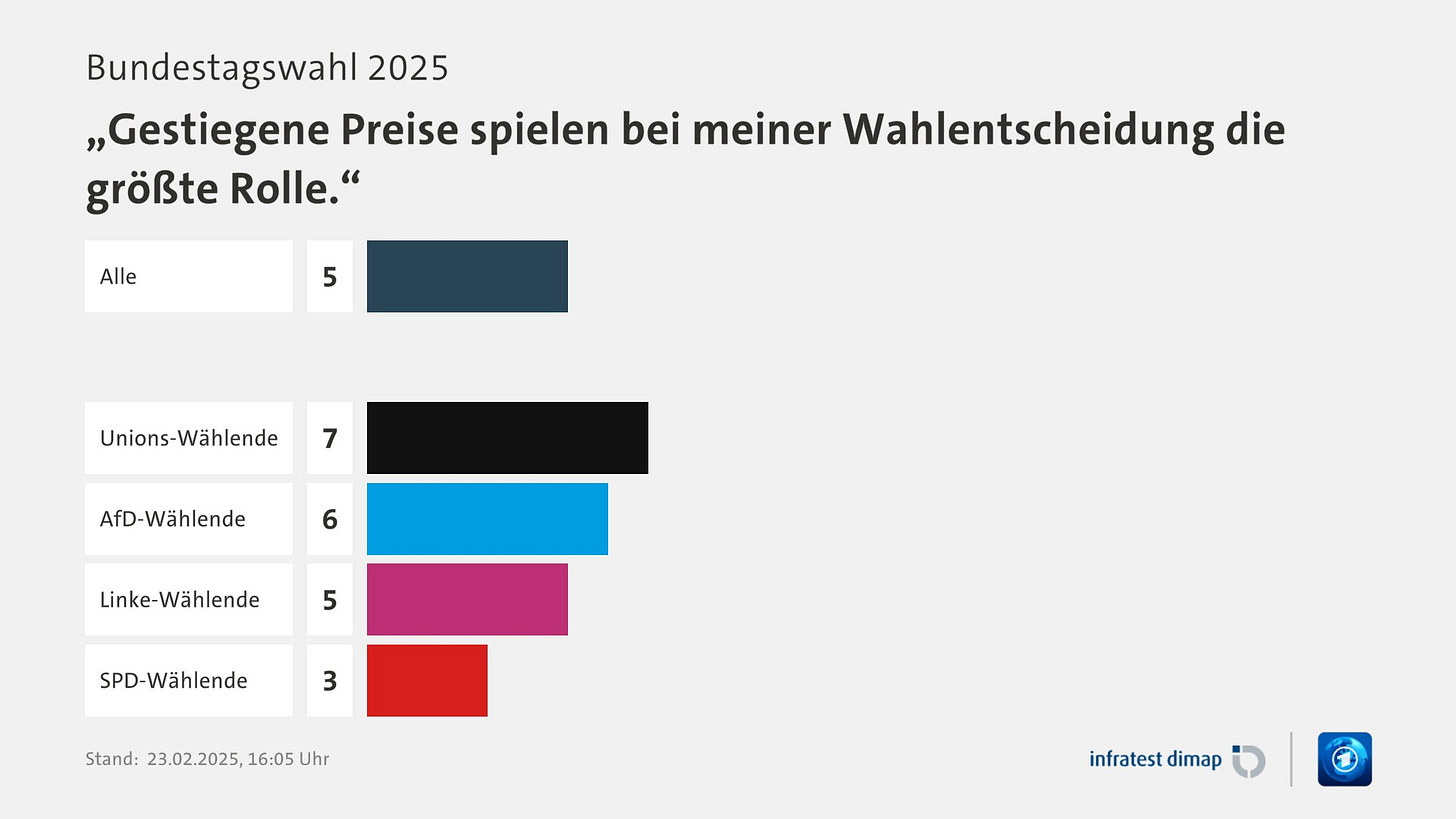

Returning to the recent German elections, there is a basic empirical issue with the inflation-centered explanation: A poll conducted by infratest dimap, published on election day, showed that when AfD voters were asked, “Which issue plays the biggest role in your voting decision?,” 38 percent answered “immigration,” 33 percent answered “internal security,” while only 8 percent chose “economic growth” and 6 percent “rising prices.” AfD voters, when pressed to pick their defining issue, largely didn’t opt for the economy, but chose either nativism or law-and-order concerns. And when all voters were asked the same question, only 5 percent placed inflation first; on this point, AfD voters didn’t diverge from the wider body politic.

Furthermore, as the chart below shows, as in the United States pre-November 2024, Germany’s inflation is nowhere near its 2021-2022 peak. So again, an inflation-centered account must consider how the memory and sensation of inflation were activated within political consciousness.

One could claim that while inflation might not have been number one on most voters’ list of self-reported priorities, including AfD voters, inflation could have contributed to the wider political-economic climate that in turn allowed immigration, nativism, and xenophobia to combine into a virulent stew. Inflation would then serve as the hard economic backdrop against which other “cultural” issues, like immigration or “safety,” could play out and rise to the forefront of public consciousness—on the thesis that an economically anxious population is more likely to be receptive to exclusionary messaging about foreign or non-native Others.

While it would be difficult to find clinching evidence for such mechanisms, economic issues weren’t unimportant to German voters: 53 percent of those polled reported that “I’m very worried that prices will rise so much that I won't be able to pay my bills,” while 48 percent were “very worried” that they would no longer be able to maintain their living standard, suggestive of real economic, inflation-driven concerns in half the voting population.

And while that might seem like definite proof of the inflation-as-backdrop idea, this risks getting the ordering exactly wrong: For what if it isn’t inflation that’s driving nativism, but nativist provocations that are fueling fears about the economy?

One suggestive piece of evidence in this direction is that while 48 percent of German voters were “very worried” that they wouldn’t be able to maintain their living standards, only 17 percent of voters were similarly worried that they would lose their job. Even more tellingly, while 83 percent of all voters rated the country’s economic situation as poor (schlecht), a whopping 67 percent of AfD voters reported that “My personal economic situation is good.”

These seemingly puzzling disconnects—between a sense of deteriorating “living standards” yet a simultaneous felt job security, and between the whole country’s perceived “economic situation” and one’s own personal economic situation—are the product of repeated messaging: about the “threat” of immigrants living on the dole, taking up precious public resources, burdening the welfare state, attacking the core values of society, spreading insecurity and criminality, and so on. Narrativization is the only sensible way of accounting for the fact that many far-right voters report feeling economically secure while simultaneously believing that the country is, somehow, collapsing around them.

Return to the discourses!

The problem with inflation-centered explanations for the rise of far-right politicians is that, without precision and refinement, they risk lapsing into a reductive form of vulgar materialism that fails to take seriously the communicative, symbolic, cultural, and discursive nature of politics. The domain of the political is also a language game, a game of signs, involving processes of symbolic construction, whereby issues do not merely “exist” out there in reality, in prefabricated form, ready to be plucked from the tree of ideology: Reality also has to be actively constructed by willing political agents; the sense of “what really matters” is also in part epiphenomenal to politicians’ processes of manufacturing and manipulation of our sense of reality.

In other words, discourses are autonomous, and discourses are not reducible to brute economic facts—if we can even speak of economic facts as independent from political construction and sense-making: Our perception of economic realities is always in part a product of how the media, political class, experts, and so on speak about the economy, and is not just a matter of how much money sits in one’s account or how much one has left over at the end of the month. We inhabit a world of mirrors, which is to say, a world of discourses.

As the anthropologists Vito Laterza and Louis Römer show in a recent essay, communication counts, and Trump’s 2024 campaign was rooted in a skillful process of narrative construction more than in “objective” economic realities:

During Trump’s 2024 re-election campaign, the momentum of the culture war helped him warp objective reality into a fantasy world where the American economy allegedly reached near catastrophic status, and migrants were to blame for virtually every ill of American society – from high housing costs to the opioid crisis, from low wages to gun violence.

Material realities count, of course, and this isn’t to deny the reality of economic pain that many ordinary people have experienced at the tail end of the neoliberal revolution that began with Reagan and Thatcher in the 1980s. But the realm of the symbolic isn’t just some superstructure to be dismissed out of hand. The game of signs, signifiers, and signification can take on a life of its own, even at times even becoming completely divorced from any economic base. Human beings are cultural, political, sign-making animals, and therefore almost infinitely malleable.

Again, this isn’t to say that economic facts don’t create a receptivity to particular kinds of messaging. At certain historical junctures, voting patterns can be heavily influenced by economic “facts.” But we ignore the autonomous reality of political communication at our own peril. Politicians can activate economic resentments by constructing narratives around the Other. Both Trump and the AfD in Germany (aided and abetted by Elon Musk) have fused economic anxieties with nativist resentments to great effect in recent months. We do ourselves a disservice if we reduce their labor of symbolic manipulation to a kind of economic determinism.

TheoryBrief Links

Thank you for reading The Theory Brief. Here are some other things worth reading and thinking about this week:

NBC News: House GOP panel passes budget blueprint with $4.5 trillion in tax cuts and steep spending reductions

CNN: USAID to lay off 2,000 employees and put most remaining staff on administrative leave | CNN Politics

Washington Post. Trump again raises idea of running for an unconstitutional third term

The Guardian: US Senate passes budget resolution to fund Trump’s deportation plan

Bloomberg: DC Would Make a Great 51st State

NY Times: Bernie Sanders Isn’t Giving Up His Fight

Reuters: China seeks stronger cooperation with Germany and EU | Reuters

Futurism.com: Economist Warns That Elon Musk Is About to Cause a "Deep, Deep Recession"

Unpopular populists?

Americans want to see Elon Musk wielding less influence, a recent poll suggests: 43% say he should have no influence at all; and while 59% think he has “a lot” of influence, only 16% think he should possess this degree of influence.

In addition, much of what Trump has done so far is deeply unpopular, according to a Washington Post-Ipsos poll:

•57 percent say Trump has “exceeded his authority since taking office.”

•Those who strongly oppose Trump’s actions in his first month “outnumber those who strongly support by 37 percent to 27 percent.”

•Trump’s approval rating is falling: 53 percent disapprove vs. 45 percent who approve of the president.

Returning to The Brink

The 2019 documentary, The Brink, on Steve Bannon and his transnational network of far-right allies, is well worth a revisit. While at times approaching a kind of aestheticization of Bannon, which therefore risks romanticizing him, the film nevertheless pulls back from the brink of its subject’s own abyss to reveal the hollowness of globalized nationalism(s).

Thank you for reading The Theory Brief. Click below to like, share and subscribe.