The Gourmand as Class Warrior

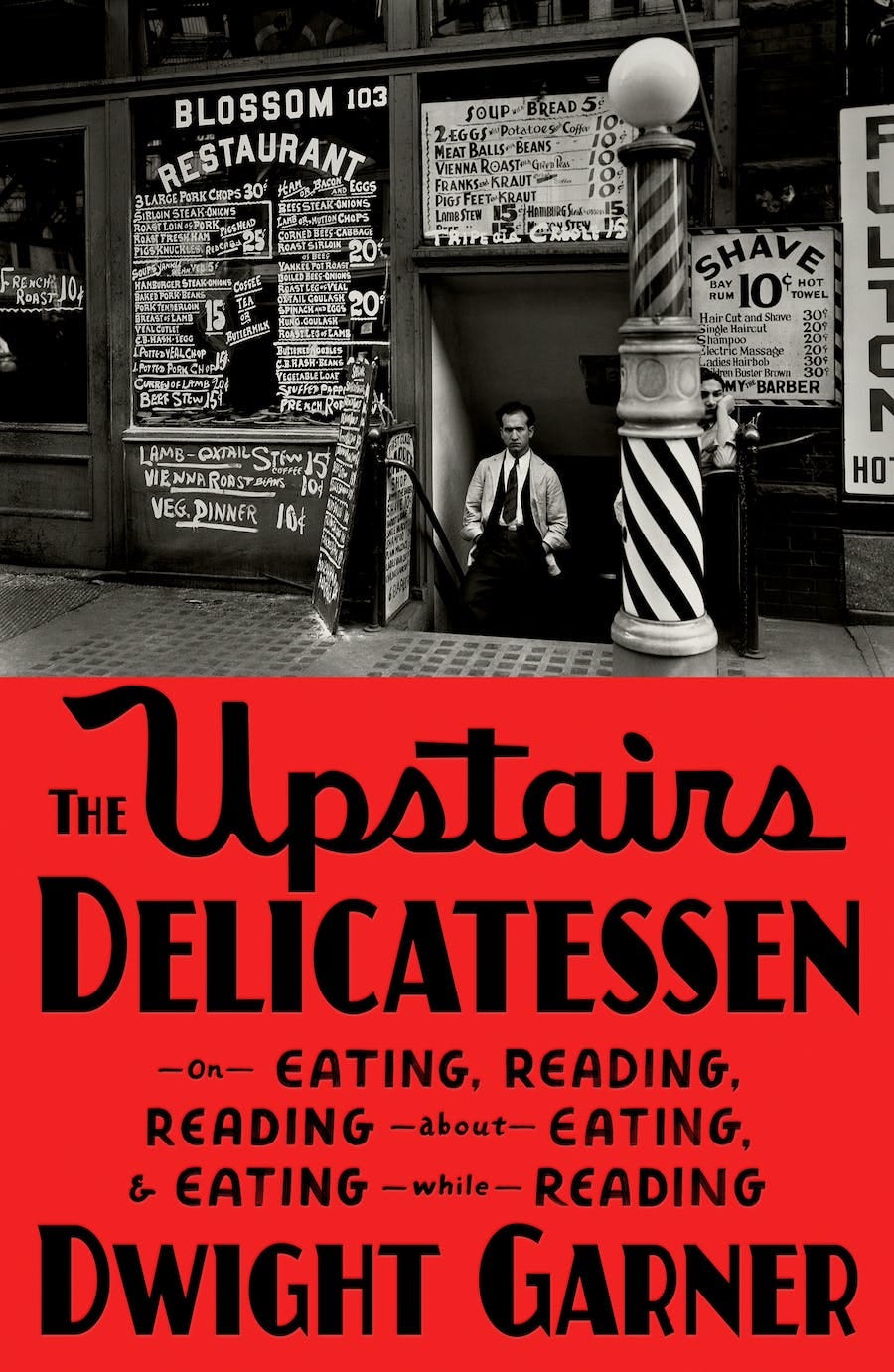

Dwight Garner (2023), "The Upstairs Delicatessen: On Eating, Reading, Reading About Eating, and Eating While Reading." New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux.

Dwight Garner (2023), The Upstairs Delicatessen: On Eating, Reading, Reading About Eating, and Eating While Reading. New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux.

There’s much jocularity in The Upstairs Delicatessen, New York Times book critic Dwight Garner’s witty, if meandering, literary-cultural commentary on two seemingly unlikely topics: novels and eating. Garner’s Delicatessen, as the subtitle lightheartedly proclaims, is a book “on eating, reading, reading about eating, & eating while reading.” But while nominally weighing in on literature and food, the book is also a poignant meditation on meatier topics, like class, culture, place, and power.

Garner repeatedly returns to the point of his origins, in the Rust Belt state of West Virginia, perhaps more nostalgic than authentic, given his relatively early adolescent relocation to sunny Naples, Florida. But food and books allow Garner to portray the tensions inherent to any ambiguous class identity, skewering the pretensions of the urban intelligentsia and cultural elites along the way. Against the foibles of the foie-gras class, Garner ruminates longingly on the wonders of West Virginian cuisine, from industrially processed fried bologna sandwiches to other homegrown culinary delectables like “peanut butter and pickle” sandwiches, another Depression-era West Virginian staple on Garner’s telling. This fare contrasts deliciously with the culinary silliness of Microsoft millionaire Nathan Myhrvold’s “molecular dining,” all fifty courses of which ultimately leave Garner unsatisfied when he is invited to partake; a cheap cheeseburger from a fast-food joint is finally needed to scratch the author’s caloric itch.

As an outsider’s insider, Garner never seems to forget, for long anyway, that he is finally a stranger to the cultural establishment, even after his decades-long tenure as a book reviewer for distinguished publications like the aforementioned Times and the New York Review of Books. Thus, Garner writes approvingly (and tellingly) of the Australian poet Les Murray: “I like a lot of things about him: his wit, his jumbo intellect, the essential wildness of his vision. I like his class politics, which speak to someone who is sometimes made to feel the cultural cringe of coming from West Virginia.” Perhaps you have to be an outsider to see the field of power, as sociologists sometimes call it, including the cultural establishment, in truer colors.

While we can agree with the Times’s own reviewer, who describes the book as a “bricolage” (a polite term for any rambling, slightly disjointed work of art), it is nevertheless Garner’s clear-sighted, almost Goffmanian attention to crisp, everyday anthropological detail that makes the book so refreshing. There are perhaps too many disembodied books about literature, but there can be little that is more embodied, after all, than a belly to fill. Garner shows that what are we really talking about when we talk about food is the body in all its myriad permutations, but also, therefore‚ the classed nature of bodies, which carry a near-infinite variety of seemingly personal—but actually deeply “socialized”—tastes and preferences. Garner is doing cultural sociology, almost Bourdieu-style, without professing any high-flying theories about consumption and socioeconomic power. It also doesn’t hurt that it’s an at times hilarious read. He carefully scrutinizes all the variegated and classed meanings of food and eating, with all the late-modern malaises (of obesity, over-eating, faddish diets, etc.), excesses (the snobbery of “fine dining”), and social distinctions (farm-fresh vs. processed food) involved in the seemingly simple act of chewing down one’s daily chow.

Only with the kind of structural cultural analysis of a sociologist like Bourdieu can we make sense of what Garner means when he says that in West Virginia, “grapefruit is as popular…as solar power.”

During the Depression, relief trains filled with grapefruit came into Appalachia, and people had no idea what to do with them. People ate them raw and thought their mouths would never unpucker. Archie’s family tried to boil them, he told me. They fried slices in grease. West Virginians have long cultural memories.

Of course, grapefruit is not just grapefruit, but a symbol (of elevated tastes, of outside meddling in internal affairs, of poverty vs. wealth), just as solar power is not just solar power alone, but the thing-in-itself plus all that it stands for in a wider set of relations of power and signification. A political movement that fails to reckon with the cultural-sociological force of such semiotic relations is, quite simply, toast.

In places, the book devolves into mere miscellanies, teetering dangerously on the brink of turning into a catalog of curiosities. But it’s also a hugely fun tour of recent and not-so-recent literary fiction. And there is, as suggested, a great deal of seriousness behind the fun. The Upstairs Delicatessen is something like an invitation to the joy of physical, sensate life. On Garner’s account, this involves reminding his readers that they lead bodily lives. With the arrival of hyper-digital late modernity, we increasingly live so abstractly—data-driven, always-connected, socially distanced (even after the passing of the pandemic)—that it is almost a shock to the system to witness this effervescent middle-aged writer plead for innocently corporeal pleasures, which seem almost old-fashioned. There is a great, healthy charm in the mode of existence Garner maps out here—not the health of the calorie counters or year-round joggers, to be sure, but the salutariness of joy, which, Garner seems to affirm, must in some sense be a joy of the flesh. In this way, too, he is reminiscent of a figure like Bourdieu, the sociologist of “flesh and blood” par excellence.

In all his celebrating of honest, cheap, authentic, homely fare, Garner also gives a deeper political lesson:

When I can’t muster the energy to cook at lunch, I make a baptismal bowl of Campbell’s tomato soup, from the can. I grew up on it. […] I use whole milk and add a pat of butter. Ideally this is consumed alongside a grilled cheese sandwich. It’s redolent of all that is good in the world. In The Making of the President 1960, Theodore H. White reported that, while boarding a plane after campaigning in West Virginia, John F. Kennedy “called for a favorite drink—a bowl of hot tomato soup.”

There’s that West Virginia upbringing again, and its celebration, against the apparent artifice of the East Coast elites. Curiously, of course, nobody was more élite, and more blue-blooded, than JFK. Still, in that unpretentious bowl of hot tomato soup, there was a folksiness, a popular charm. It might have been fake. It probably was fake. But if you want to understand political leaders who have successfully won over that great American heartland, the Midwest and the Rust Belt—derisively labeled “fly-over country” by some insiders—you have to try to understand that bowl of hot tomato soup, and all that it signifies.